Recursive queries in relational databases

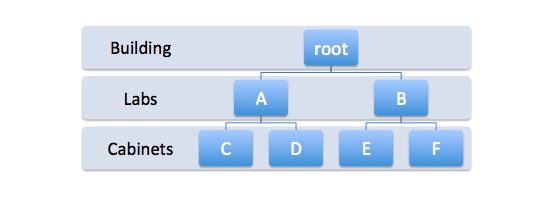

Generally, businesses are modeled in hierarchies. There's a CEO, Vice Presidents, General Managers, all the way down to the lowly engineers. But that's beside the point. Because of this feature of businesses, we often seek a way to model our data in hierarchical ways. Take, for example, a hierarchy of authorization groups. Group A and Group B have mutually exclusive sets of authorizations - A can enter lab A and B can enter lab B, but neither can enter each others' labs. Group C and D are part of Group A, but each have unique sets of permissions. So Group C has access to cabinet C only in lab A, and Group D has access to cabinet D only in lab A.

Here's our simplest problem statement: How do I find all the children of a given group?

To begin answering this question, we can model our hierarchy as a tree.

Each group can be modeled as an object with properties:

class Group

{

Group parent;

Permission[] perms;

}

group table:

+----------+------------+-------------+-----------------+

| group_id | group_name | permissions | parent_group_id |

+----------+------------+-------------+-----------------+

| 1 | root | ... | null |

+----------+------------+-------------+-----------------+

| 2 | A | ... | 1 |

+----------+------------+-------------+-----------------+

| 3 | B | ... | 1 |

+----------+------------+-------------+-----------------+

| 4 | C | ... | 2 |

+----------+------------+-------------+-----------------+

| 5 | D | ... | 2 |

+----------+------------+-------------+-----------------+

| 6 | E | ... | 3 |

+----------+------------+-------------+-----------------+

| 7 | F | ... | 3 |

+----------+------------+-------------+-----------------+

group_relationship table where

we can model all the different types of relationships between groups (parent, child, etc.), but for the purposes of this post

our solution will allow us to reference just one table, as we'll soon see.

Naive approach

The first naive approach that comes to mind is use a wrapper procedural language around SQL (let's use python), and write a

simple database call get_children(group_name) that returns all the children groups of group_name.

We'll call it from a recursive method:

# returns a set of children group names

def get_all_children(group_name):

children = set()

for child_group_name in get_children(group_name):

children |= get_all_children(child_group_name)

return children

SQL approach

We'd like to take a similar approach as before, only in SQL. In come Common Table Expressions (CTE's), or in postgres, WITH queries.

The [postgres doc]: http://www.postgresql.org/docs/8.4/static/queries-with.html "postgres docs" have a great resource on how these work, but I'll give a short overview here.

CTE's are like sub-queries. Let's say we want the user names of all members of lab groups (A or B). In postgres:

SELECT DISTINCT u.user_name

FROM (

SELECT *

FROM group

WHERE group_name in ('A','B')

) as l

JOIN user_group_relation r ON r.group_id=l.group_id

JOIN user u ON u.user_id=r.user_id;

WITH labs_only as (

SELECT *

FROM group

WHERE group_name in ('A','B')

)

SELECT DISTINCT u.user_name from labs_only l

JOIN user_group_relation r ON r.group_id=l.group_id

JOIN user u ON u.user_id=r.user_id;

l with a CTE named labs_only.

But here's the cool part: CTE's can also refer to themselves, and this ability makes them a prime tool for recursion. Postgres has the descriptor keyword

RECURSIVE reserved for the purpose. The structure of a WITH RECURSIVE query is like so:

WITH RECURSIVE t(n) AS (

[non-recursive term]

UNION / UNION ALL

SELECT [recursive term f(n)] FROM t WHERE [condition]

)

Finally, here's our solution to the group hierarchy problem:

WITH RECURSIVE recursive_group AS (

SELECT *

FROM group

WHERE group_name='A'

UNION

SELECT g.*

FROM group g, recursive_group rg

WHERE g.parent_group_id=rg.group_id

)

SELECT group_name from recursive_group;

-

Declare the CTE

recursive_groupsas recursive - Initialize the non-recursive value as the row representing group 'A'

-

Perform a union on the 'building table' started by the non-recursive value, and the table

returned by the recursive value. In the recursive value

WHEREclause, our condition is that the previous group's id should equal the next group's parent_id

Pitfalls

One possible pitfall is if two groups are each others' parents. This creates a circular path in the tree resulting in an infinite loop on the database.

A thought on business logic

As Martin Fowler writes in Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, "there are few things more illogical than 'business logic'". It is a natural jump for business people to have Group D access some area of lab A, only on Tuesdays, and when revenue growth is below 50%. While our hierarchy model doesn't totally break down, as software engineers we have to be wary of customizations to our oversimplified rules. These "outlets" to plug logic into have to be built in from day one, or they cause big problems down the road.